Reading Like a Copyeditor

The Wind in the Willows and the Whole Book Approach

Warning: This is a long one!

Happy National Reading Month, and welcome to another collaboration of Missing Pieces and Strike-Through. For those of you who don’t know, we’re sisters with a passion for history and English literature and grammar.

Today we’re delighted to feature one of the most iconic children’s books of the twentieth century, The Wind in the Willows. In fact, Kenneth Grahame’s charming book celebrates its 115th birthday this year in October.

Rachel will start with some historical background on Grahame and The Wind in the Willows before turning it over to Rebekah, who will introduce the Whole Book Approach and use it to analyze the book.

Then—depending on the newsletter to which you subscribe—you’ll get a special section about either Theodore Roosevelt’s thoughts on The Wind in the Willows, which came out during his presidency, for Missing Pieces or an analysis of illustrations in the book for Strike-Through.

If you don’t already subscribe to both of our newsletters but would like to, check out Missing Pieces (written by Rachel Lane) here and Strike-Through (written by Rebekah Slonim) here.

It All Started with a Letter

You probably don’t know that The Wind in the Willows originated from a series of letters that Kenneth Grahame wrote to his beloved son. Grahame, who was a bank teller—officially the secretary of the Bank of England, dreamed of being a storyteller and wrote in his free time. In the late 1800s, he published Dream Days and Golden World. After his literary success, he married Elspeth Thompson in 1899. They welcomed their only child Alastair a year later.

When Alastair was seven years old, the Grahames took a long vacation, leaving their son at home with his nanny. Kenneth promised to continue his bedtime story tradition with Alastair—through letter. Kenneth sent fifteen letters featuring the adventures of Badger, Mole, Rat, and Toad to his son in the spring of 1907 while he was away.

After they returned, Elspeth encouraged her husband to compile the stories into a book. Upon his retirement from the bank in 1907, Kenneth turned the letters into The Wind in the Willows. Almost called The Wind in the Reeds, Grahame’s book was published in October 1908. Although his other books had been popular, The Wind in the Willows cemented Grahame’s reputation as a well-known author.

As A. A. Milne notes in an introduction to the book, “It is a Household Book; a book which everybody in the household loves, and quotes continually; a book which is read aloud to every new guest and is regarded as a touchstone of his worth.”

Today I (Rebekah) am going to provide some guidance on how we should go about reading The Wind in the Willows, or other books, whether aloud or silently.

Introducing the Whole Book Approach

One Saturday last fall, I was browsing the library when I came across a book that I instantly knew I was encountering “at the right time, the right place, and the right mood” (see below graphic).

The book was called Reading Picture Books with Children by Megan Dowd Lambert. When I found the book, I had just begun homeschool preschool with my son Ezra and was wondering how to make our times of reading aloud more enriching and how to answer his abundance of questions whenever we opened a book.

Lambert doesn’t talk about copyediting in her book, but she presents a way of reading aloud that she calls the Whole Book Approach—and it perfectly suits the way copyeditors learn to approach texts.

In Lambert’s words, the “Whole Book Approach [WBA] simply stresses inviting children to react to the whole book—its art, design, production, paratextual and textual elements—in ways that feel natural and enriching to them and to you as the adult reader.” (Paratextual elements are parts of the text that are in addition to the main text of a book, like the cover or afterword.)

When you read according to the WBA, you read the whole book: from the dedication page to the endpapers. You talk to the kids about the terms for various elements of a book, like “facing pages” and “gutter” and “headers.” You discuss how the pictures interface with the text. You answer the questions children have as they interact with the book.

Why the WBA Suits Copyeditors

Copyeditors and proofreaders also use a similar approach while reading. No element of a book can or should escape our notice. And after years of faithfully reading the dedications and appendixes and headers and page numbers in all the manuscripts we copyedit, we start caring about all those details in the other books we read. While the WBA is focused on picture books and reading with kids, it does have a broader application.

After being introduced to Lambert’s paradigm, I quickly incorporated elements of WBA into both read-alouds for our more formal preschool time (we use this curriculum for literature) and more generally. Ezra took to it immediately. Frequent WBA-inspired questions and comments in our household include: “What’s going through the gutter?” “There’s the copyright page and then the dedication page.”

I had a proud moment one day when Ezra, sitting down to read a pretend book, first read the title on the pretend cover and then read the title on a pretend title page.

Why read the title twice? Why point out the copyright page to an eighteen-month-old? Why stress the presence of an afterword to a four-year-old?

Doing such things teaches us to pay attention. In many picture books, the story really starts on the endpapers. That’s where the artist might introduce his color scheme, for example. We’re missing part of the story if we don’t attend to the whole book. We can get more out of books—more meaning, more learning, more enjoyment, more delight—if we pause at the dedication page and at least flip through the footnotes.

So, how might you start reading using the WBA?

The WBA and The Wind in the Willows

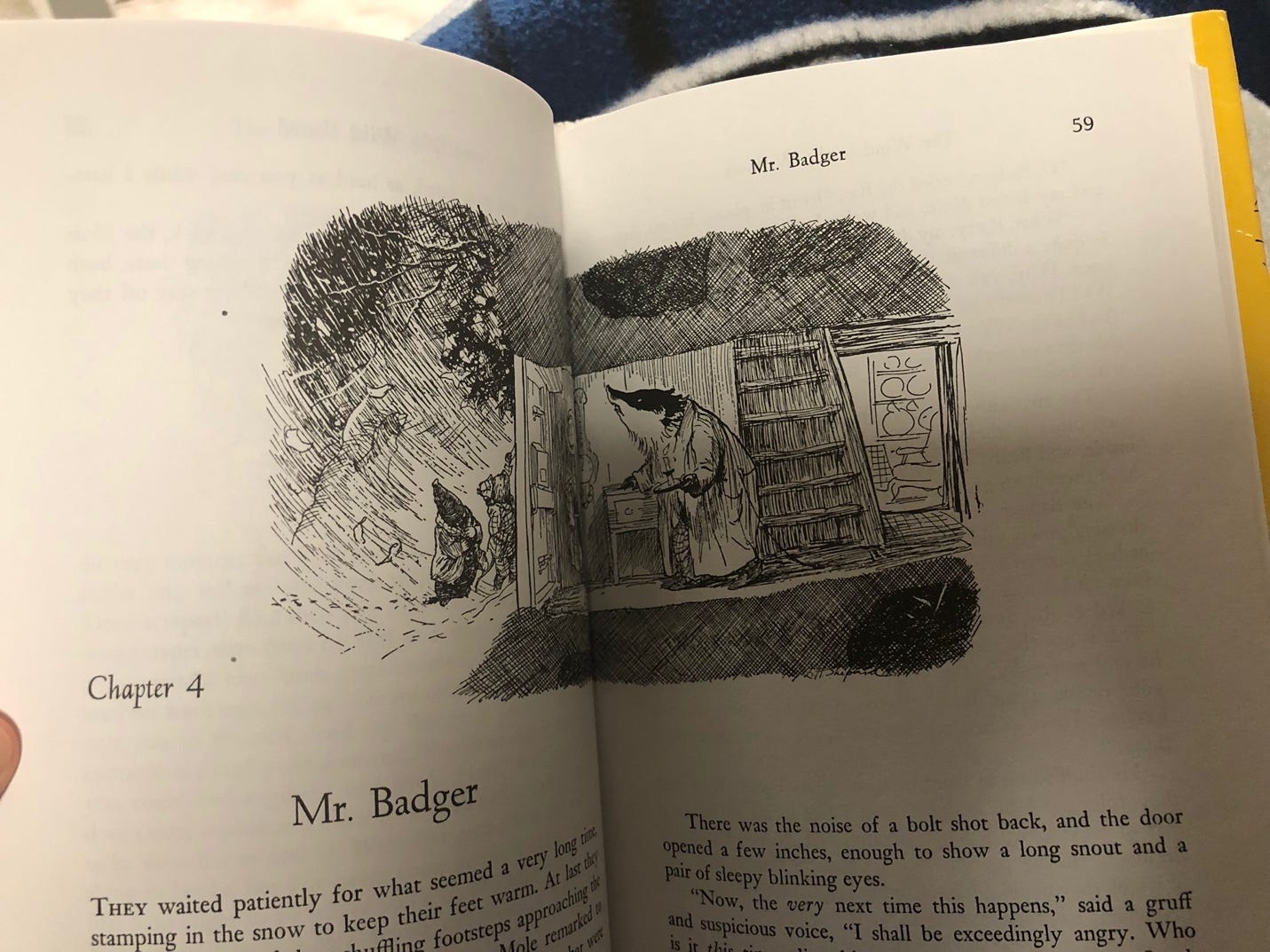

Let’s return to The Wind in the Willows. I am examining the edition illustrated by Ernest H. Shepard, which was first published in 1931.

“Kenneth Grahame’s dreamy tale of Rat, Mole, Toad, and Badger—and their life along the riverbank—may just be the most insightful guidebook in the English language to deep and lasting human relationships. After reading The Wind in the Willows, one longs to be a better friend.”

—Dr. Daniel B. Coupland, Chairman and Professor in Education at Hillsdale College

I read this book with great enjoyment when I was eight years old. I got it for Christmas in 2001 but didn’t begin to read it until the following spring. The description of Mole spring cleaning that begins the book left an indelible impression—it seems so perfectly springlike, as if the essence of spring had somehow been captured in this beautiful book. And it made me think that Mole was the central character of the book, at least at first.

Well, perhaps I should have been employing the Whole Book Approach!

Who is that reflecting at the table, pen in hand, on the title page? It’s Rat! So Rat, in some sense, is the author of this story. It also suggests that the events about to be related are past ones—ones that Rat is recollecting. The theme of memory and nostalgia, which is important in the story, is already at work before the main text has begun.

(Of course, a little reader or listener might not be able to make quite so many inferences. But, as Lambert says, you might be surprised what kids will come up with if invited to respond to a text.)

Moral of the story—don’t skip the title page!

This page evokes the mood of summer—the words of the text gently glide down the page to reflect how in the illustration Rat is relaxing. Text and illustration work together.

The text and the illustrations aren’t silos to be examined separately. Instead, the text and the illustrations create meaning greater than the sum of their parts.

Don’t just look at the text and the illustrations—look at how they interface.

Here, the text and the illustration are more separated from each other in a perfect “What’s going through the gutter?” page.

The act of noticing the gutter—defined as “the blank space down the center of an open book where the pages are bound together”—when an illustration is going through it helps me to take the picture in more.

In this illustration, the gutter underscores Mole and Rat’s long, patient wait at the door as they hear Mr. Badger’s “shuffling footsteps.”

It’s Your Turn to Apply the WBA

I hope these quick examples are an encouragement to you to take a least a moment to linger at the dedication page or stop for a minute or two at the opening of a chapter.

Learn the terminology of publishing, from the physical elements of a book to the types of punctuation (I hope all my readers could recognize an em dash!), and simply pay attention.

I think you’ll find reading like a copyeditor worthwhile.

Beating through the thicket of English, while pausing to watch what’s going through the gutter,

Rebekah Slonim

Thank you for sharing about the Whole Book Approach! Although we enjoyed many whole books as my children were growing up, I hadn't figured out to notice the copy page, or some of the other details you mention. Now I need to start noticing what I've missed!